July 26th, 1998

Does Size Really Matter?

By Jackie Giuliano, Ph.D.

Who

took the dream of the land

who staked down "private property"

through the soul of the deer

who diverted streams

cleared forests

burned fields

I

seek to know

my own name

I

seek to know

why

after all that I have done

to her

does the Mother continue

to embrace me

-- Charlie Mehrhoff

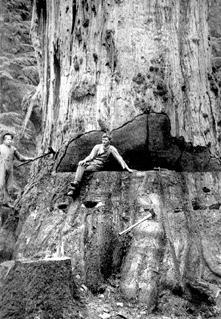

This tree was reportedly the largest tree in Washington State (Photo taken in

1906 from "This Was Logging" by R. Andrews, 1954)

You have to work really hard to cut a tree this size down. Of course it is only fair

that it should take many hours to destroy something that has taken a thousand years to

grow.

It is so painful sometimes to realize that virtually our entire Western culture is built

on the principle that humans were put here to dominate nature. How we view our forests

provides some insight into this troubling mindset.

There has been much controversy over the importance of big trees. Lumber companies

salivate at the sight of them. People will strap themselves to the ancient giants to

prevent them from being cut down. What is going on? What's all the fuss?

California Coast Redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens) are the world's tallest known trees and

among the oldest. These giants last for hundreds of years partly because their wood has a

natural resistance to fungus, disease, and insect damage because of its high tannin

content. Their thick, fibrous bark has even more tannin than the wood and helps the trees

resist fires. These redwoods can live more than two thousand years.

Imagine a tree that has lived long enough to have been around when Stonehenge was being

built, when the sundial was invented, when Plato taught students - a tree that has seen

humans on our journey from the times of wandering tribes to our travels to the other

planets.

Path in the Ho Rainforest in Olympic National Park, Washington State (photo (c) Jackie

Giuliano, 1998)

Few remaining forests on Earth are "old growth," that is, they contain the

original ecosystem and all of its diversity. Most people who have seen forests, even dense

ones, are probably looking at second or third growth. Most of our lands have been cleared

or logged one or twice in their history.

When you are in an old growth forest, you can feel it. The colors are deep, deep green,

the growth is dense, there is an amazing diversity of plants, and there are fallen trees

everywhere, many with other trees growing out of them. Everything feels alive, intense.

Attempting to justify why we should preserve old-growth forests is difficult and

represents the classic dilemma in environmental management. By Western conventions of

economic health, they are a resource that is here now that can be sold and a profit that

can be made. By these rules, as long as you have a buyer, it is OK to harvest a resource.

This ethic has operated for over 2,000 years. During that time, resources appeared to be

unlimited. The supply of trees, minerals, and wildlife seemed inexhaustible.

In ecological history, this belief is referred to as the Myth of Superabundance. It never

really was true, but to resource-starved immigrants from England to the world they called

New, the resources seemed endless.

Humans have placed ourselves (erroneously) at the top of the food chain, and from this

lofty position, nothing is safe from our grasp.

Photo (c) Jackie Giuliano, 1998

Old-growth forests are a unique kind of ecosystem. The diversity of life they contain

is unparalleled. One of the most important aspects of them may be the fallen trees they

contain. From these come complex nutrients for new soil, a birthplace for new trees, and

homes for many species.

We devalue such objects and call them "dead" and "fallen" and

"litter" and "clutter," thereby further separating ourselves from the

cycles of life. Without these deaths, there can be no life.

Seventy-six countries have already lost all their old growth forests. The U.S. has already

lost 96 percent.

5,000 people rally in Humbolt, California in September 1997 to save the Headwaters

Forest (From Rainforest Action Network website)

But in Northern California, a 60,000 acre remnant of a temperate rain forest exists, a

rain forest that just 200 years ago covered two million acres of the California coast from

the Oregon border to Big Sur. In this acreage are 6,000 acres of old growth forest with

trees like the one pictured above. This forest lives completely on private property, owned

by the Pacific Lumber Company.

Why preserve old growth? Statistics and facts can be manipulated to produce any outcome,

so we have to look to our hearts for the answer.

Maybe we should preserve them because it is the right thing to do. Maybe by preserving the

last stands of these trees that have watched the human species grow for the last two

millennia, we can show the universe that we know when it is time to say

"enough."

Maybe if we decide to let these giants live, we will have the chance to sit down by them

and just listen to what they have to say. What might they say to you?

RESOURCES

1. Participate in the campaigns to save the last remaining old-growth forests at the

Rainforest Action Network web site at http://www.ran.org/ran/ran_campaigns/old_growth/index.html

and learn about the Headwaters Forest at http://www.ran.org/ran_campaigns/redwood/background.html

2. Ecologists estimate that in order for the 6,000 acres of old growth in the Headwaters

forest to survive, the entire 60,000 acres must be preserved. Learn what you can do at http://host.envirolink.org/headwaters-ef/

3. Learn of immediate things you can do to save old growth by changing our building and

consuming habits at http://www.ran.org/ran/ran_campaigns/old_growth/taking_action.html

and http://www.ran.org/ran/ran_campaigns/old_growth/call.html#opport

4. Learn about tree-free paper at http://www.ran.org/ran/ran_campaigns/old_growth/kenaf_fact.html

and buy some.

5. Learn about redwoods and the efforts under way to save them from the Save the Redwoods

League at http://www.savetheredwoods.org/r_res/rrmain.htm

6. Learn more about the clearcutting problem from the Wilderness society at http://www.wilderness.org/standbylands/forests/paying.htm

7. Find your Congressional representatives and e-mail them. If you know your Zip code, you

can find them at http://www.visi.com/juan/congress/ziptoit.html

and tell them you want them to save the old growth forests.

8. Learn about the issues. Seek out books on the subject. A good source for used (and new)

books is Powell’s Bookstore in Portland, Oregon at http://www.powells.com/cgi-bin/associate?assoc_id=212

where you will find a wonderful alternative to the massive chain bookstores taking over

the market.

9. Visit the owlcam at http://members.aol.com/owlbox/nest98.htm

to see a family of owls living and raising their young. Remind yourself of the miraculous

cycles of life. Updated daily. |